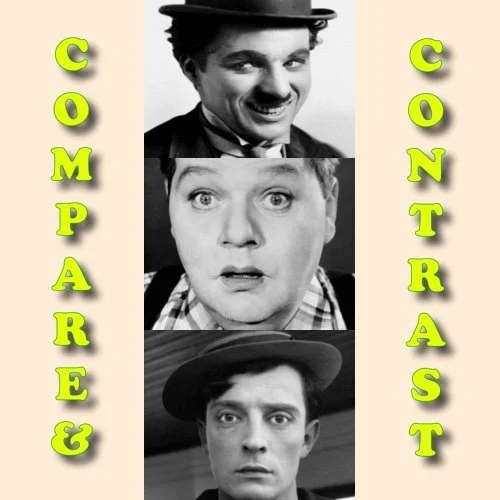

Compare And Contrast: Charlie / Fatty / Buster

If you’re like me -- and you damn well better be, or else this post will be an exercise in futility -- you long admired the pioneering clowns of the silent screen.

Most people covering the silent era focus on the Big Four: Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Harry Langdon.

But’s that’s the wrong end to start with. They were the top comedians in the late 1920s, but by then silent comedy had almost three decades to hone its craft.

To me the earlier silent comedies are more interesting. They show the medium being literally invented on the fly with stories that appeared to be improvised on the spot. Going back to the dawn of the silent era we find only three names that are dominant: Charlie Chaplin, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, and Buster Keaton.

It’s a fool’s errand -- and not the good kind -- to try to say which is best. They’re like items on a menu. Some people will always prefer one more than the others.

So I’m not going to rank them, I’m just going to show their particular style and skills and encourage you to hunt them down online.

Fortunately for this exercise, we have three short comedies by each performer that cover roughly the same territory, so we can more easily compare apples to apples: Fatty Joins The Force (1913), Charlie Chaplin in Police (1916), and Buster Keaton in Cops (1922).

First off, a caveat:

Buster here enjoys a slight advantage over the earlier films. Hollywood became a cinematic boom town in the six years between Police and Cops, the technical polish brough to films in the 1920s clearly distinguishes them from earlier efforts. On top of that, Fatty Joins The Force is not primo Arbuckle, and Police is only mid-grade Chaplin while Cops is Keaton at damn near the top of his form.

The Performers:

Physically these are the three greatest silent comedy performers. Their visual slapstick is absolute perfection. Keaton is the most extreme in his physical comedy, doing insane Jackie Chan-level stunts (famously he broke his neck doing one stunt for Sherlock Jr. and still finished the picture!). Chaplin, conversely, scales his physical comedy down but adds a touch of grace the others lack (W.C. Fields once referred to Chaplin as the greatest ballet dancer who ever lived). But pound-for-pound, Arbuckle almost matches Keaton despite his enormous bulk and girth. Call this one a three-way tie.

Their Characters:

Each had an iconic stock character they played in almost every movie they made, and surprisingly, not a very virtuous character. All three demonstrated themselves fully capable of petty larceny in their stories, willing to lie and mislead to gain an advantage.

Ironically, this marked each of them as an Everyman. People could identify with them because they weren’t goody-two-shoes who held themselves to be superior but rather regular schmoes beset with the same problems and challenges as their audience -- albeit it turned up to eleven.

And there’s no false happy endings, either. Fatty Joins The Force ends with Fatty weeping in jail, Police ends with Chaplin free but running away from a pursing policeman, and Cops closing title card indicates Keaton is dead.

Their Stories:

Fatty Joins The Force and Police look cruder than Cops, but as mentioned above, the very medium was evolving right before our eyes. The story elements in Fatty Joins The Force really don’t logically connect to one another, it’s more like they lurched from one gag to another, tenuously linked only by involving police in some form.

This is characteristic of most Arbuckle short comedies I’ve seen. There are arbitrary set pieces he liked doing again and again, the main action frequently forgotten while following some unimportant side character, and in many occasions additional scenes that serve nothing but padding.

Cops is like one of those domino videos where each toppling tile leads to a bigger and more chaotic complication. It’s probably the best paced comedy Keaton made.

Police, on the other hand, features a much more emotional story. Chaplin -- freshly released from prison -- repeatedly faces temptation to return to a life of crime. Dragooned by an old cellmate into burglarizing a house, Chaplin halfheartedly goes along. When the cellmate threatens the lady of the house -- title cards say she’s trying to keep him from robbing her sick mother upstairs but the action looks far different from that -- Chaplin steps in and protects her. She in turn tells the police when they finally show up that he is her husband. Saved from going to jail, Chaplin sets off to start life anew…

…only to run into a policeman he encountered earlier in the film and the chase is on once again.

Police is also innovative in its filmmaking using shadows to tell the story in once scene and managing to convey Chaplin’s character while doing so, and sight gags inside the burglarized house that force the audience to “hear” the ruckus Chaplin and his cellmate are making.

In Summary:

As I said above, there’s no right or wrong / best or worst in this comparison. Arbuckle made better films than Fatty Joins The Force; unfortunately, his career got cut short by a scandal in which a young actress attending a drunken party he threw – this during Prohibition – resulted in audiences rejecting his films and him being virtually blacklisted (he died in 1933 just after restarting his career in the sound era). Chaplin made far better films than Police, but they’re like comparing grand slam home runs to a double; the former’s more spectacular but the latter gets the job done. Keaton’s later silent comedies are uniformly brilliant and his features even better, with The General being one of the best films of the silent era. During the sound era he drank himself into an insane asylum but Chaplin brought him back to co-star in the comedy-drama Limelight and that sparked renewed interest in his career and got him back in front of the cameras again, finishing his career spearing in various Beach Blanket movies in the 1960s -- and typically being the funniest thing in them.

So take your pick -- or better yet, take them all. They were bona fide geniuses in their time.

© Buzz Dixon

![SOFT vs FIRM [FICTOID]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/590697e7d1758ec4d7669624/1751258138852-RIVK7SFZKQ7TU7S4PYNM/FT+306+SOFT+vs+FIRM+-+John+T+McCutcheon+art+SQR.jpg)

![Rock-A-Beatin' Boogie [FICTOID]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/590697e7d1758ec4d7669624/1746339570917-WMQLUP20DQFGXZ5VS7IH/FT+305+Rock-A-Beatin+Boogie+SQR.jpg)