Art Ain’t A Mirror, It’s A Hammer (Part 2 of 3)

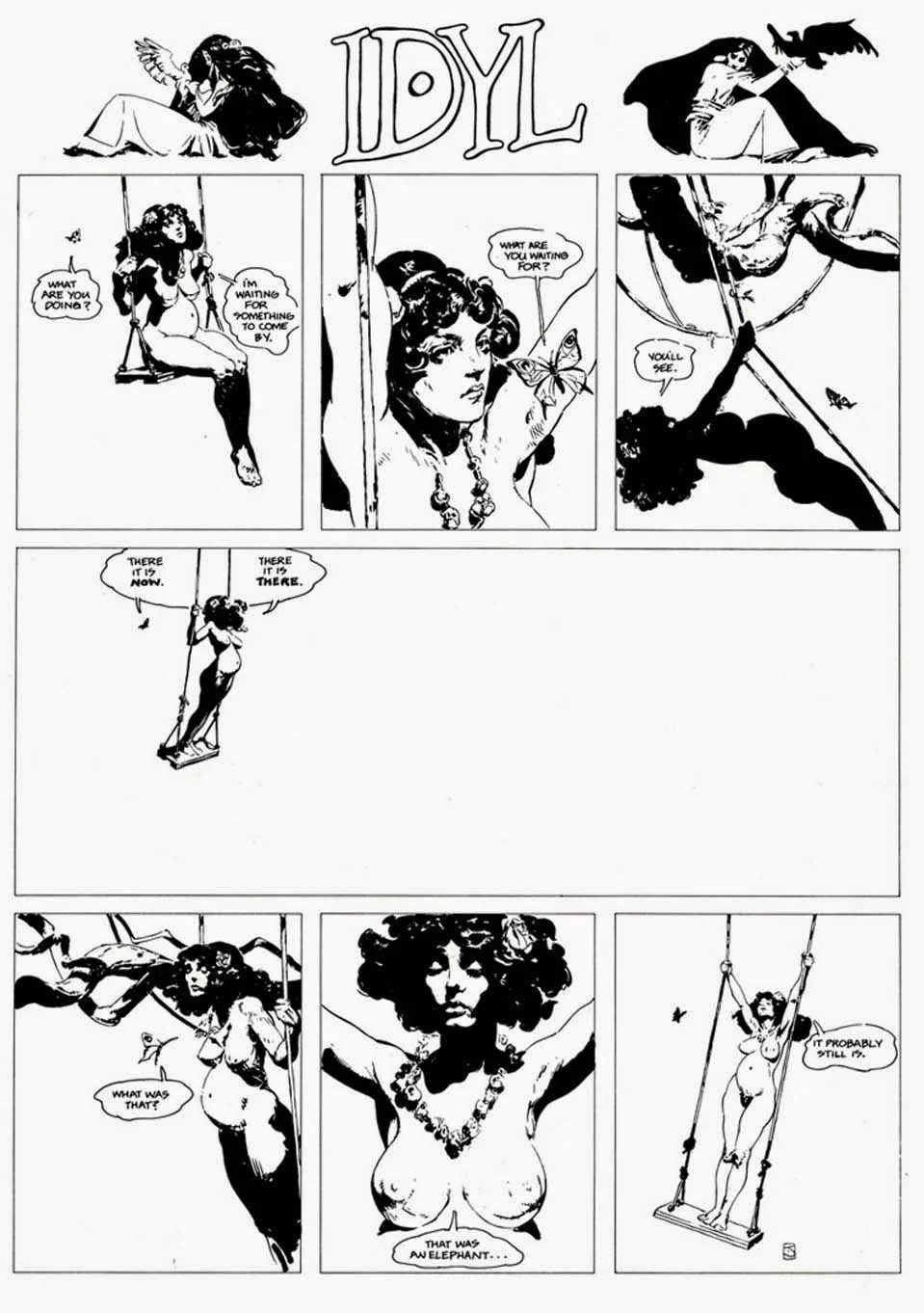

From 1972 to 1975, the artist now known as Jeffrey Catherine Jones drew a one-page comic strip for National Lampoon entitled “Idyl.”

To call “Idyl” enigmatic would be far too clinically precise a term.

As Jones famously explained, “I kept handing them a hole, waiting for them to ask for a donut to go along with it.”

Recently I got on a Waiting For Godot kick and began tracking down various performances online.

Waiting For Godot is Samuel Beckett’s famous theater-of-the-absurd play. Unlike Eugène Ionesco’s equally famous and equally absurd Rhinoceros, Beckett’s play lacks anything that might remotely be considered a story.

Ironically, this helps explain the play’s popularity. It’s easy to mount on stage, it’s crammed with amusing incidents and bits of business that actors delight in hamming up, and there’s no pesky plot to keep track of.

It means nothing -- and such was Beckett’s intent.

This does not preclude audiences from trying to attach as much meaning to it as possible.

The most common interpretation is a religious allegory, with the never seen character Godot simply a roman a clef for God.

Yeah, could be.

But it’s open to numerous other interpretations as well, and the various performances I’ve seen range all the way from tragic existential angst to low brow knockabout Laurel & Hardy style comedy (Stan & Ollie being acknowledged inspiration for the work).

So which is correct?

There’s a certain post-modern / quantum mechanics feel to Waiting For Godot. Beckett offers no meaning the audience can react to, they must supply their own.

The result is an infinity of possible interpretations, because as in the quantum universe, the moment one observes something, one collapses all the myriad other possibilities of what it could be into a single concrete thing -- none of which prevents the next observer from collapsing it into something entirely different.

In a way it is very much anti-art.

While art (in the conventional sense) usually implies a creator with a specific meaning or message attempting to pass this along to their audience, Beckett forgoes that.

To paraphrase the

Firesign Theatre,

he might as well say,

“In this world, you’re

on your own.”

But as Quant demonstrated (and oh, how deliciously ironic her name is in this context), what the artist means, what they intend is not necessarily what the audience will derive from it.

Art becomes art not when the artist creates it, but only when the audience perceives it, be they one or one billion.

. . .

Which drags us -- kicking and screaming -- to the matter of AI “art”.

Despite its presumptive name, AI is not Artificial Intelligence.

Rather, it’s a very clever technology that can analyze existing human creativity and combine it in unexpected ways.

In principle it’s no different than Musikalisches Würfelspiel, the old German dice game where random throws set precomposed music into various different arrangements.

While one could argue the individual movements contain meaning since they came from human creativity, the final arrangement as a whole does not because it’s only a random assemblage of bits and pieces.

“But, Buzz,” you say, “don’t humans mix & match / cut & past / downright plagiarize as well?”

Yup, we sure do.

For a reason.

We blend different ideas together with intent to produce a new synthesis, something that takes divergent concepts and produces something new from it.

We steal, but with a purpose.

AI doesn’t do that, and arguably may never do it.

As Gertrude Stein once observed, “There’s no there there.”

AI no more produces art than nature does (and obviously by art we include all forms of traditionally human creativity).

Nature produces incredibly beautiful things, but we as humans bring the beauty to what we see or hear by our judgment.

Nature provides no meaning, it simply is. We can enjoy the fresh smell of a field of flowers, the dazzling colors of a sunset, the songs of birds but ultimately they are just particles and energy.

The beauty we attach to them comes from within us.

What marks human art -- good / bad / indifferent -- apart from nature is that we create with a purpose, to communicate some idea or emotion we value.

There were sunsets on earth for billions of years before the first eyes evolved. Without someone to see them, how could they be beautiful?

And yet when someone paints a picture or even takes a snapshot of a sunset, they are attempting to communicate to others what they find beautiful and awe inspiring.

If they store it in a file they never open again, is it really art without an audience?

© Buzz Dixon

![Nobody Tosses Salads Like Sandra [FICTOID]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/590697e7d1758ec4d7669624/1685389981461-VPL3LW6WGBZ8Q55UTEPB/FT+168+Nobody+Tosses+Salads+Like+Sandra+SQR.jpg)

![Rooster Guitar [FICTOID]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/590697e7d1758ec4d7669624/1684911086304-6J18PHRQMZIP4G5VLQJ0/FT+168+Jim+Flora+-+Rooster+Guitar+SQR.jpg)